| |

When I was in graduate school getting my masters in fine art, I learned an important concept pertaining to how artists create. As I was writing one of the early drafts of my thesis, one of my committee members suggested that I write about my process. Being a painter who loved painting on birch panel, this meant describing my actions from how I selected choice three-quarter inch birch plywood to how I applied various layers of paint until the piece was complete. Initially, I fought the idea because I could not see the value in it. However, being a person who understands the importance of human interaction and dialogue, I followed my committee members suggestion. What I experienced, after writing extensively on my methodology, was one of the most revealing moments in the development of my artistry. I noticed that I approached the craftsmanship of my work the same way I approached my notion of self. In other words, I was doing to my panels physically what I was doing to myself psychologically. Recognizing the connection between my life and art was central to my understanding the vital role art plays in responding to and shaping my sense of being.

While re-writing and re-editing my thesis, I noticed that one of the recurring themes inherent in my process was the notion of redemption. Redemption, in its broader sense, refers to the act of getting something back to its rightful owner -- renewing it to its place of origin. Growing up in a Christian home, redemption was a word very familiar to me. My family viewed Jesus Christ as the one who got us back from Satan and returned is to God through the shedding of his blood on Calvary. In order to acknowledge being redeemed one must first buy into the idea that one is not in ones proper place. One would necessarily have to view ones current state of being as substandard, horrible, shameful, or even grotesque. One must admit that they are less than what they should be. When I take this principle into account, it is not difficult for me to see the roles that low self-esteem and self-loathing play in shaping what I do in life. The more I pondered my process the more I became aware of how I saw myself. This was a revelation to me because I thought I had a healthy view of myself.

What I wrote in my thesis involved my selecting what I considered to be the best birch panel. Smooth and organic, birch panel was extremely seductive. I liked it in its natural state so much that it was always a challenge for me to begin sanding it and preparing it for painting. Its beauty stood on its own with no help from me. However, if I wanted to make a painting out of it, I had to mar its surface with sandpaper, then gesso and then sandpaper again. I did this ritualistically until the primed panel was as smooth as (if not smoother than) what it had been in its natural state. I had redeemed it. This marring/redemption cycle repeated itself with every layer of paint I applied to the panel until the final stage of redemption (the completion of the piece) had been reached. The hate-love relationship that I witnessed in my process, I began to see in the perception I had of myself. Each painting I completed successfully gave me a reason to value myself. I realized that painting is something I constantly have to do to affirm my importance to the human community.

Recently, I met an artist whose work reflected this same notion of redemption. Like me, she painted in oils but her body of work was, I initially thought, quite different from mine. Her background, experiences, education, aesthetic consumption, and intellectual appetite seemed a world apart from mine. However, when I talked extensively with her and listened carefully to the things she said, I realized that we were very much alike in how we approached our art and our lives.

Before I met Toni Taylor, I was told she painted fantasy art and I wanted to see her work. I have never been a fan of fantasy art (the subject matter never appealed to me) but I know that a good fantasy artist knows how to handle paint well. They have to. My initial interest was in seeing her work up close so that I could take apart her painting techniques to see which ones I could use in my own works. However, when I went to her home to view the works, an unexpected feeling crept into my being. It was a feeling of familiarity. I could not explain to myself what I was experiencing. I could not put my finger on it. Of course, her paint handling was everything I expected it would be but I was getting something more from the works. For some reason, the question kept popping into my head Why would a person paint these particular images with these particular themes? I was not sure why I was intrigued but I allowed the questioning to take root in my psyche.

Toni Taylor's art is unlike any other fantasy art I have seen. It stems from a personal, private mythology that is hybrid in its conception and execution. Like water being squeezed from a sopped sponge, references from various cultures (ancient and contemporary), ideas from various mythologies, and icons from various belief systems pour from each piece. Toni Taylor's work is sensual. It is its own determinant, its own judge. It does not ask to be anything more than what it is even though it hints at universality. I began asking Toni Taylor questions about herself, her childhood, her artistic influences, and anything else that came to my mind. I was fascinated with what her work was doing to me and I wanted to know from whence it came. Toni Taylor shared with me. She held nothing back. She answered all my questions as thoroughly and as honestly as she possibly could.

Our conversations did not happen all at once. They happened over a period of two weeks. In one of our conversations, I shared with Toni Taylor my experience in graduate school and the insight it gave me into myself. She and I both agreed that what is in an artists soul will surface in the work if that artist created honestly. I knew her work was telling me something about her even though it was elusive. Sitting in her home the last time we met, surrounded by her works and listening to her ruminate about her past, I figured out why her work initially intrigued me. It was about redemption. The way our conversation had gone that day, I ended up asking her something like Given what you have experienced in the past, what are you trying to accomplish in doing all these paintings about all this stuff? Her response was something like I guess I am trying to redeem myself from my past life. Upon that revelation our eyes locked wide open on each other and we both said Aaah, redemption! The connection was made.

|

Year of the Dragon, by Toni Taylor. All rights reserved. |

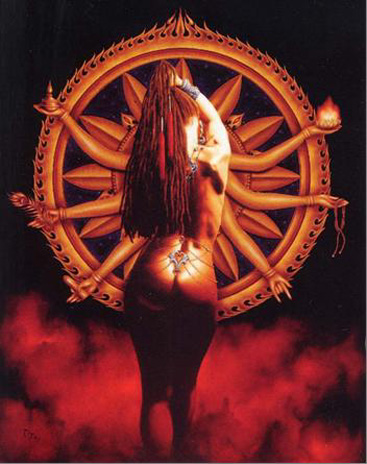

Tantrika, by Toni Taylor. All rights reserved. |

Whereas redemption resides in my process, it resides in Toni Taylor's choice of characters and subject matter. Collectively, her work focuses primarily on the female. Whether hybrid creatures that are half woman and half dragon, depictions of goddesses from various belief systems, or just pure figments of her fascinating imagination, her females are almost always aggressive in their femininity, sensuous in their demeanor, and seemingly empathetic to all living organisms. In Year of the Dragon, Toni depicts a bronze-skinned, feminine creature that is half human and half dragon. Crawling on all fours with arms and legs, the terminal extremities of her limbs are not hands and feet but razor-sharp talons. With silver mane flowing from the crown of her horned head down to the tip of her serpentine tail, the creature is shown descending from a celestial crystal mountain with a huge red pearl clutched in her left talon. According to the artist, the pearl she is carrying is the Pearl of Wisdom from Chinese lore. It can only be won through trial and transformation from what was to something better. Herein lies the concept and process of redemption in Toni Taylor's subject matter. Similar ideas about transformation and renewal surface in many other works albeit through different characters and different mythologies.

Although the being in Year of the Dragon is half human and half dragon, one does not get a feeling of fear and uneasiness from her animalistic characteristics. On the contrary, she appears seductively aggressive (although not in the sense of a femme fatale). With her head slightly down and her eyes upturned at the viewer, she is unapologetic in her sensuality. One can see a similar aggressiveness in Tantrika. A Tantrika is a practitioner of the sacred art of Tantra (an Eastern art form which takes intimacy to its highest level, fulfilling spirit as well as body). While the subject matter here is a woman standing before a six-armed sculpture representing symbols of Tantra, the directness of her posture and the details of her taut physique emanate an aura which is a world apart from passivity. Tantrika is about the females authority over her own sexuality, which, in the case of Tantric influences, is sacred and set apart for only the cosmically worthy. That these women are physically and emotionally adept, gracefully and beautifully sexual, and gently nurturing in their demeanor is a testament to the artists aspirations for redefining how people see women. In these characterizations, Toni Taylor has redeemed woman from the prison of stereotypes people often associate with the female gender.

I have said to my students, on many occasions, that when writing essays they must write honestly. While good grammar and diction are essential to quality writing, writings are much more effective when they represent the soul of the writer. Creating art bears the same principle. If one is not an interesting person, their art will not be interesting. Artists who create honestly and share their secret places with viewers have a good chance (regardless of subject matter) to connect with a kindred, parched soul. This is the highest function of human creativity. It reminds us of our dependency on one another as human beings and it affirms our value to the quality of human life.

In trying to redeem ourselves, I think that deep down inside what Toni Taylor and I are trying to do is redeem humanity. This redemption is from what we perceive to be destructive tendencies that slowly erode human compassion and empathy. The undesirable attributes we have (or have had) buried in our own psyches are but manifestations of a much larger human condition. This is our arts greatest challenge and its most noble effort. It serves the purpose of redeeming us specifically and, through that process, emitting a vibrant glow that screams quietly enough to awaken another disillusioned soul. The more we redeem ourselves the more we can redeem others. Redemption through our art is perhaps one of humanitys most saving graces.

Editor's note: Toni Taylor's studio (www.tltart.com) is located in the heart of Orlando, Florida. Trent Tomengo (ttomengo@yahoo.com) is a visual artist based in the Orlando metro area and a professor of Humanities at Seminole Community College in Sanford, Florida.

The text content of this article is the intellectual property of Trent Tomengo and may not be copied or re-published without consent. Toni Taylor holds all copyright rights to the images above which may not be copied or re-published without consent

|

| Back to Home Page I Back to Previous Page I Back to Top |

Brian Owens

(T) 386-956-1724

© 2004 Brian R. Owens |

|

brianowensart.com |

(T)386-956-1724 |

|